Shorthand

In 1626, Thomas Shelton revised a stenographical system begun by John Willis. In Shelton’s shorthand system every consonant was expressed by an easy symbol which sometimes still resembled the alphabetical letter. The vowels were designated by the height of the following consonant.

Thomas Shelton’s shorthand

Thomas Shelton’s Shorthand Alphabet

A disadvantage of Shelton’s shorthand was that vowels and dipthongs were not always distinguished. For example, the symbol for bat could mean “bait” or “bate” as well. This can only be decided from the context. An advantage of his system was that it could be easily learnt.

Shorthand experienced the heights of popularity during and immediately following the Civil War. By the early 1890’s, the century’s practice of producing verbatim speeches in the newspaper was on the wane, and this reduced the need for the most skilled stenographers. Readers preferred more interpretation of great speeches and the happenings of Congress.

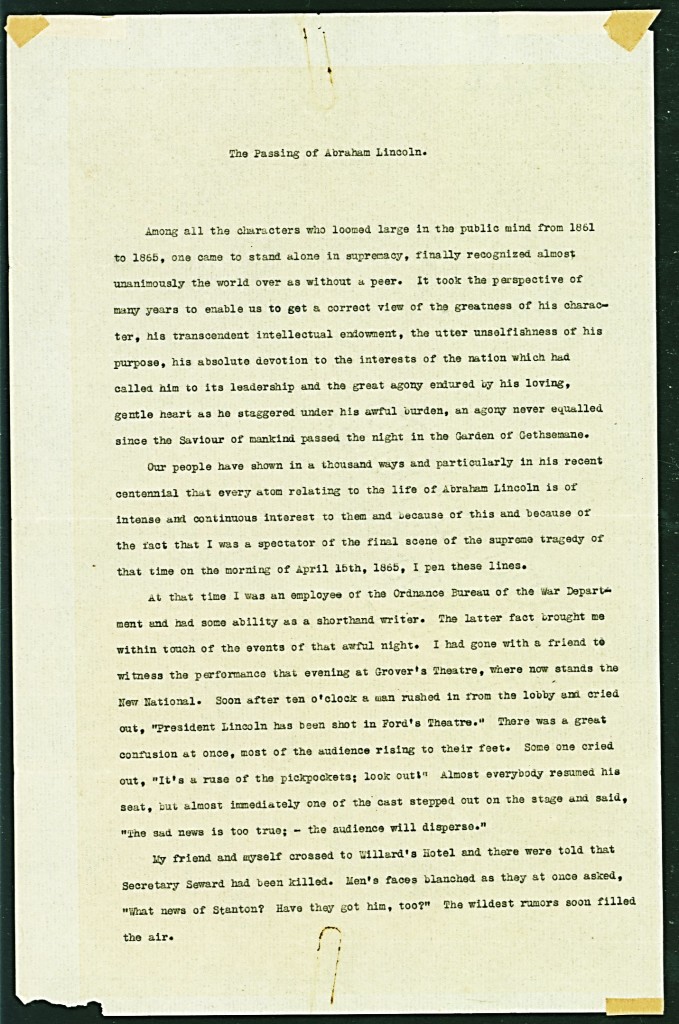

Tanner Letter

This transcription was copied from the original document and is representative of all spelling, punctuation, and grammar as written by the creator. The original document is housed in the Pearce Civil War Collection, Pearce Collections Museum, Navarro College, Corsicana, Texas. https://www.PearceMuseum.com

The Passing of Abraham Lincoln.

Among all the characters who loomed large in the public mind from 1861 to 1865, one came to stand alone in supremacy, finally recognized almost unanimously the world over as without a peer. It took the perspective of many years to enable us to get a correct view of the greatness of his character, his transcendent intellectual endowment, the utter unselfishness of his purpose, his absolute devotion to the interests of the nation which had called him to its leadership and the great agony endured by his loving, gentle heart as he staggered under his awful burden, an agony never equaled since the Saviour of mankind passed the night in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Our people have shown in a thousand ways and particularly in his recent centennial that every atom relating to the life of Abraham Lincoln is of intense and continuous interest to them and because of this and because of the fact that I was a spectator of the final scene of the supreme tragedy of that time on the morning of April 15th, 1865, I pen these lines.

At that time I was an employee of the Ordnance Bureau of the War department and had some ability as a shorthand writer. The latter fact brought me within touch of the events of that awful night. I had gone with a friend to witness the performance that evening at Grover’s Theatre, where now stands the New National. Soon after ten o’clock a man rushed in from the lobby and cried out, “President Lincoln has been shot in Ford’s Theatre.” There was a great confusion at once, most of the audience rising to their feet. Some one cried out, “It’s a ruse of the pickpockets; look out!” Almost everybody resumed his seat, but almost immediately one of the cast stepped out on the stage and said, “The sad news is too true; – the audience will disperse.”

My friend and myself crossed to Willard’s Hotel and there were told that Secretary Seward had been killed. Men’s faces blanched as they at once asked, “What news of Stanton? Have they got him, too?” The wildest rumors soon filled the air.

I had rooms at the time in the house adjoining the Peterson House, into which the President had been carried. Hastening down to Tenth Street, I found an almost solid mass of humanity blocking the street and the crowd constantly enlarging. A silence that was appalling prevailed. Interest centered on all who entered or emerged from the Peterson House and all of the latter were closely questioned as to the stricken President’s condition. From the first the answers were unvarying, – that there was no hope.

A military guard had been placed in front of the house and those adjoining but upon telling the Commanding Officer that I lived there, I passed up to my apartment, which comprised the second story front of the house. There was a balcony in front and I found my rooms and the balcony thronged by the other occupants of the house. Horror was in every heart and dismay on every countenance. We had just about a week of tumultuous joy over the downfall of Richmond and the collapse of the Confederacy and now in an instant all this was changed to the deepest woe by the foul shot of the cowardly assassin.

It was nearly midnight when Major General Augur came out on the stoop of the Peterson House and asked if there was any one in the crowd who could write shorthand. There was no response from the street but one of my friends on the balcony told the General there was a young man inside who could serve him, whereupon the General told him to ask me to come down as they needed me. So it was that I came into close touch with the scenes and events surrounding the final hours of Abraham Lincoln’s life.

Entering the house I accompanied General Augus down the hallway to the rear parlor. As we passed the door of the front parlor the moans and sobs of Mrs. Lincoln struck painfully upon our ears. Entering the rear parlor, I found Secretary Stanton, Judge David K. Carter, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, Honorable B. A. Hill, and many others.

I took my seat on one side of a small library table opposite Mr. Stanton with Judge Carter at the end. Various witnesses were brought in who had either been in Ford’s Theatre or up in the vicinity of Mr. Seward’s residence. Among them was Henry Hawk, who had been Asa Trenchard that night in the play “Our American cousin”, Mr. Alfred Cloughly, Colonel G. V. Rutherford and others. As I took down the statements they made we were distracted by the distress of Mrs. Lincoln for though the folding doors between the two parlors were closed, her frantic sorrow was distressingly audible to us.

She was accompanied by Miss Harris of New York, who, with her fiancé, Major Rathbone, had gone to the theatre with the President and Mrs. Lincoln. Booth in his rush through the box after firing the fatal shot had lunged at Major Rathbone with his dagger and wounded him in the arm slightly. In the naturally intense excitement over the President’s condition, it is probable that Major Rathbone himself did not realize that he was wounded until after he had been in the Peterson House some time, when he fainted from loss of blood, was attended to, his wound dressed, and he taken to his apartments. He and Miss Harris subsequently married.

Through all the testimony given by those who had been in Ford’s Theatre that night there was an undertone of horror which held the witnesses back from positively identifying the assassin as Booth. Said Harry Hawk, “to the best of my belief, it was Mr. John Wilkes Booth, but I will not be positive,” and so it went through the testimony of others but the sum total left no doubt as to the identity of the assassin.

Our task was interrupted very many times during the night, sometimes by reports or dispatches for Secretary Stanton but more often by him for the purpose of issuing orders calculated to enmesh Booth in his flight. “Guard the Potomac from the city down,” was his repeated direction. “He will try to get South.” Many dispatches were sent from that table before morning, some to General Dix at New York, others to Chicago, Philadelphia, etc.

Several times Mr. Stanton left us a few moments and passed back to the room in the ell at the end of the hall where the President lay. The doors were open and sometimes there would be a few seconds of absolute silence when we could hear plainly the stertorous breathing of the dying man. I think it was on his return from his third trip of this kind when, as he again took his seat opposite me, I looked earnestly at him, desiring yet hesitating to ask if there was any chance of life. He understood and I saw a choke in his throat as he slowly forced the answer to my unspoken question, – “There-is-no-hope.” He had impressed me through those awful hours as being a man of steel but I knew then that he was dangerously near a convulsive breakdown.

During the night there came in, I think, about every man then of prominence in our national life who was in the capital at the time and who had heard of the tragedy. A few whom I distinctly recall were Secretaries Welles, Usher, and McCullough, Attorney General Speed and Postmaster General Dennison, Assistant Secretaries Field and Otto, Governor Oglesby, Senators Sumner and Stewart, and General Meigs and Augur. I have seen many asserted pictures of the deathbed scene and most of them have Vice President Andrew Johnson seated in a chair near the foot of the bed on the left side. Mr. Johnson was not in the house at all but in his rooms in the Kirkwood House and knew nothing of the events of that night ‘til he was aroused in the morning by Senator Stewart and others and told that he was President of the United States.

With the completion of the taking of testimony I at once began to transcribe my shorthand notes into longhand. Twice while so engaged, Miss Harris supported Mrs. Lincoln down the hallway to her husband’s bedside. The door leading into the hallway from the room wherein I sat was open and I had a plain view of them as they slowly passed. Mrs. Lincoln was not at the bedside when her husband breathed his last. Indeed, I think, it was nearly if not quite two hours before the end, when she paid her last visit to the death chamber and when she passed our door on her return, she cried out, “Oh! my God and have I given my husband to die!”

I have witnessed and experienced much physical agony on battlefield and in hospital but of it all, nothing sunk deeper in my memory than that moan of a breaking heart.

I finished transcribing my notes at six forty-five in the morning and passed back into the room where the President lay. There were gathered all those whose names I have mentioned and many others, – about twenty or twenty-five in all, I should judge. The bed had been pulled out from the corner and owing to the stature of Mr. Lincoln, he lay crosswise on his back. He had been utterly unconscious from the instant the bullet ploughed into his brain. His stertorous breathing subsided a couple of minutes after seven o’clock. From then to the end only the gentle rise and fall of his bosom gave indication that life remained.

The Surgeon General was near the head of the bed, sometimes sitting on the edge thereof, his finger on the pulse of the dying man. Occasionally, he put his ear down to catch the lessening beats of his heart. Mr. Lincoln’s pastor, the Reverend Dr. Gurley stood a little to the left of the bed. Mr. Stanton sat in a chair near the foot on the left, where the pictures place Andrew Johnson. I stood quite near the head of the bed and from that position had full view of Mr. Stanton across the President’s body. At my right Robert Lincoln sobbed on the shoulder of Charles Sumner.

Stanton’s gaze was fixed intently on the countenance of his dying Chief. He had, as I said, been a man of steel throughout the night but as I looked at his face across the corner of the bed and saw the twitching of the muscles I knew that it was only by a powerful effort that he restrained himself. The first indication that the dreaded end had come was at twenty-two minutes past seven when the Surgeon General gently crossed the pulseless hands of Lincoln across the motionless breast and rose to his feet.

Reverend Dr. Gurley stepped forward and lifting his hands began, “Our Father and our God” – I snatched a pencil and notebook from my pocket but my haste defeated my purpose. My pencil point (I had but one) caught in my coat and broke, and the world lost the prayer, – a prayer which was only interrupted by the sobs of Stanton as he buried his face in the bedclothes. As “Thy will be done, Amen” in subdued and tremulous tones floated through that little chamber, Mr. Stanton raised his head, the tears streaming down his cheeks. A more agonized expression I never saw on a human countenance as he sobbed out the words, “He belongs to the ages now.”

Mr. Stanton directed Major Thomas M. Vincent of the Staff to take charge of the body, called a meeting of the Cabinet in the room where we had passed most of the night and the assemblage dispersed.

Going to my apartment, I sat down at once to make a second longhand copy for Mr. Stanton of the testimony I had taken, it occurring to me that I wished to retain the one I had written out that night. I had been thus engaged but a brief time when hearing some commotion on the street, I stepped to the window and saw a coffin containing the body of the dead President being placed in a hearse which passed up Tenth Street to F and thus to the White House, escorted by a Lieutenant and ten privates. As they passed with measured tread and arms reversed, my hand involuntarily went to my head in salute as then started on their long, long journey back to the prairies and the hearts he knew and loved so well, the mortal remains of the greatest American of all time, bar none.

[Handwritten signature] James Tanner

[handwritten]

To Col. John Temple [Woure?]

Tanner Letter – The Passing of Abraham Lincoln, pg. 1