Photography in the Civil War

History of Photography in the Civil War in Texas

The process of photography was discovered in France early in 1839 by Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre. The daguerreotype was introduced to America shortly thereafter, and one of its main proponents was Samuel F. B. Morse. By late 1839 a few talented individuals in New York and Philadelphia were experimenting with the process, and by the summer of 1830 the new art form had spread to many of the major American cities. It caught on quickly and spread down the Atlantic seaboard to the coastal southern states and along the Gulf of Mexico to cities such as Mobile, New Orleans, and Galveston. The earliest professional photographers in Texas operated along the Gulf Coast, and many were itinerants. As settlements were formed inland, the photographers followed.

Civil War in Texas Photographers

Civil War Photography

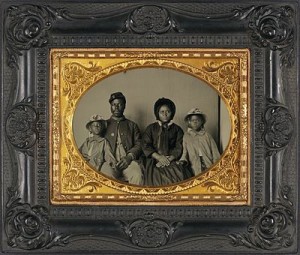

From 1840 to the beginning of the American Civil War, at least 118 photographers were working in Texas, and by 1860 many Texas communities had permanent photographic galleries. Texas was not unlike other states, both North and South, in that the Civil War crisis brought about a boom in certain types of businesses, photography being one of them. As the young men of Texas volunteered for Confederate military service, may found themselves leaving home and traveling relatively great distances for the first time in their lives. Partially to commemorate their service and departure and also to leave a memento with a loved one, it became customary for the volunteer soldier to go to the nearest photographer to have his “likeness” made. It was also a common practice for a soldier to carry one or more photographs of his wife, children, or other family member when he left home. During this period, the overwhelming majority of photographs made in Texas were studio portraits of individuals. On rare occasions, views were taken outdoors, and some scenes were produced, but examples are almost impossible to locate today.

With few exceptions, the types of photographs that were made in Texas during the Civil War were ambrotypes, tintypes, or cartes de visite portraits.

Ambrotype Photography

Ambrotype Photography

The ambrotype was a photograph made on a glass plate. Basically, it was a collodion or “wet-plate” negative that was made into a positive image when backed with black cloth, varnish, metal, or even paper. Some were even made on a ruby-colored glass that helped turn the negative into a positive photograph. Each ambrotype was one of a kind. If a soldier wanted more than one copy, he had to sit for another exposure or have the original ambrotype copied.

Tintype Photography

Tintype Photography

The tintype was also a unique wet-plate process in which the emulsion was coated on a sheet of black japanned iron to produce a positive image. The thin metal plate of the tintype was more durable than the glass plate ambrotype, and tintypes became quite popular during the war. Both ambrotypes and tintypes came in sizes ranging from 1 3/8 by 1 5/8 inches to 6 ½ by8 ½ inches. They were usually framed by a brass ma over which a protective cover glass was placed and then housed in a miniature case that further protected the fragile image.

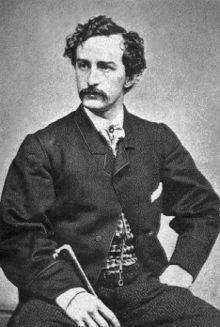

Carte de Visite Photography

Carte de visite of John Wilkes Booth; around 1863 by Alexander Gardner

Carte de visite of John Wilkes Booth; around 1863 by Alexander GardnerHowever, it was the carte de visite (French or “visiting card” or “calling card”) which surpassed all other forms of photography during the war. This form of wet-plate photography was a small size albumen paper print, usually 2 ¼ by 3 ½ inches, that was mounted on a 2 ½ by 4 inch card. The carte de visite, or CDV as it is commonly called today, involved the creation of a negative from which multiple copies of an image could be produced. That alone gave the carte de visite a tremendous advantage over earlier photographic processes, and a soldier could have as many copies made as he wished.

Civil War Photography Poses

Civil War Photography

Sometimes the soldier posed without armament or even a uniform. But, as often as not, he posed with weapons to emphasize the seriousness of his military bearing. The most common weapons seen in images of the period are long arms such as muskets and shotguns, followed by revolvers and the large personal knives known as “side knives” or Bowie knives. The Confederate volunteer sometimes was posed and photographed with a combination of all of these types of arms. In numerous instances, a photographer would supply “prop” weapons if the soldier had none available for the occasion.

Wartime Photography

As the war began to wind down, Texas Confederates slowly drifted back to Texas on foot, on horseback, and by boat. A substantial number of photographs of returning Texas Confederates were taken in cities such as New Orleans where photograph galleries were plentiful.

Itinerant photographer A.G. Wedge was operating in Galveston by April 1861. A carte de visite photograph that Wedge took of Gen. John Be. Magruder includes a Confederate first national flag as part of the design of his imprint. To date, it remains the only example of a wartime Texas photograph using an imprint that clearly indicates that this photograph was taken in a Confederate state. Wedge would eventually work his way down the southern coast of Texas and would operate in the Brownville area where he is believed to have taken studio views of Gen. Hamilton P. Bee and several members of his staff.

Within five years after the war, literally hundreds of photographers were entering Texas, and a new generation of photographic work was beginning.